India’s path to climate resilience goes beyond NDCs: Here’s why we need a legal framework for adaptation

From policy to law, crafting a comprehensive climate adaptation strategy is imperative to protect lives and livelihoods in the country

Recognising this, the Supreme Court of India, in MK Ranjitsinh & Ors vs Union of India & Ors, recently acknowledged that the fundamental Right to Life and Equality includes the Right against the adverse effects of climate change, opening the door for litigation against the state for inadequate or poor climate resilience measures.

A comprehensive adaptation resilience strategy, beyond the existing Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) and climate action plans, is urgently needed to safeguard the population, economy and ecosystems from overlapping climate impacts affecting India’s diverse geography. Fundamentally, this necessitates a transition from a policy framework to binding legislation addressing responsive climate adaptation — a legal mechanism that exercises the right recognised by the Supreme Court.

A climate law would essentially embody the Latin principle Ubi jus, ibi remedium (where there is a wrong, there is a remedy) to address climate risks. While remedies can currently be sought under the Constitution of India, specific climate legislation would streamline the process and bridge existing gaps by providing a clear framework for legal remedies to effectively address climate-related grievances.

The vagaries of extreme weather events in India have reached alarming levels, with nearly every day from January to September 2023 witnessing a disaster. Over the past 30 years since the Rio Convention, India has incurred $3,555 billion in losses due to climate change. In 2022 alone, climate impacts on infrastructure accounted for 7.9 per cent of the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), highlighting the severe economic toll of extreme weather events.

The escalating risks of disasters, diseases, loss of livelihoods, crop failures, and displacement, coupled with health, water, and food insecurity, are undermining India’s development goals. These impacts are exacerbating inequality and disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations.

The need for adaptation resilience

Climate change is a living reality, and adaptation is the process of adjusting to actual or expected climate conditions and their effects. Considering the disproportionate impacts on developing countries, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change has encouraged developing nations to establish National Adaptation Plans to protect their people and economies from climatic changes.

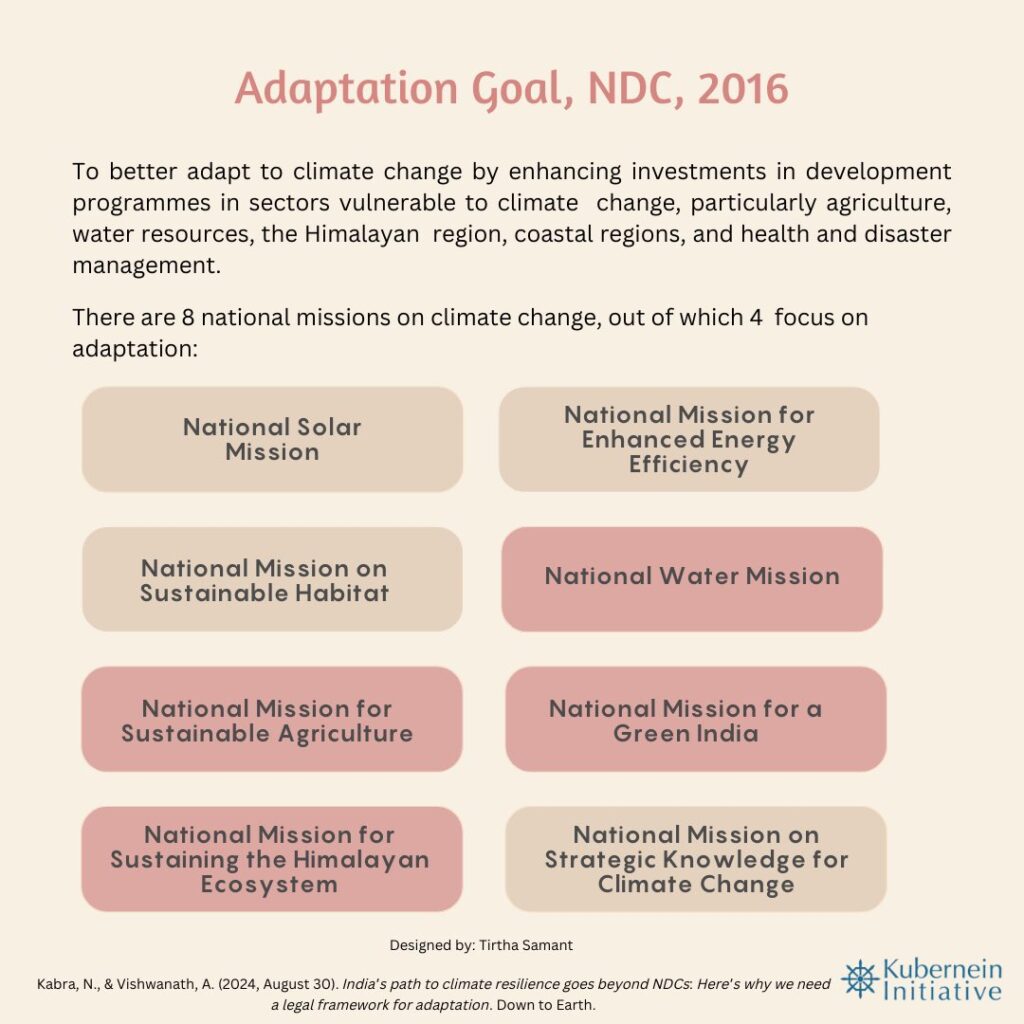

India’s climate policy framework, largely stemming from the 2016 NDC, includes targets for mitigation strategies, but adaptation targets, borrowed from the 2008 National Climate Change Action Plan, have remained unchanged. The Report of the Sub-Committee for the Assessment of the Financial Requirements for Implementing India’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), 2020 by department of economic affairs under Union ministry of finance, emphasised the necessity of intensifying India’s adaptation actions in light of its climate vulnerability — currently, approximately 2.8 per cent of India’s GDP has been spent on adaptation sectors such as healthcare, poverty alleviation and risk management.

Without a strategic adaptation plan, such expenditures remain merely symptomatic or reactionary and perpetuate recurring costs and financial strain as climate-related occurrences grow. If the resilience of people, infrastructure and the economy is prioritised through preemptive affirmative actions, it could serve to build resilience and lower long-term exposure and expenses. Key sectors such as agriculture, water, forests, biodiversity and health, among others, need to streamline climate adaptation and resilience strategies and finance.

A climate legislation with hyper-local actions

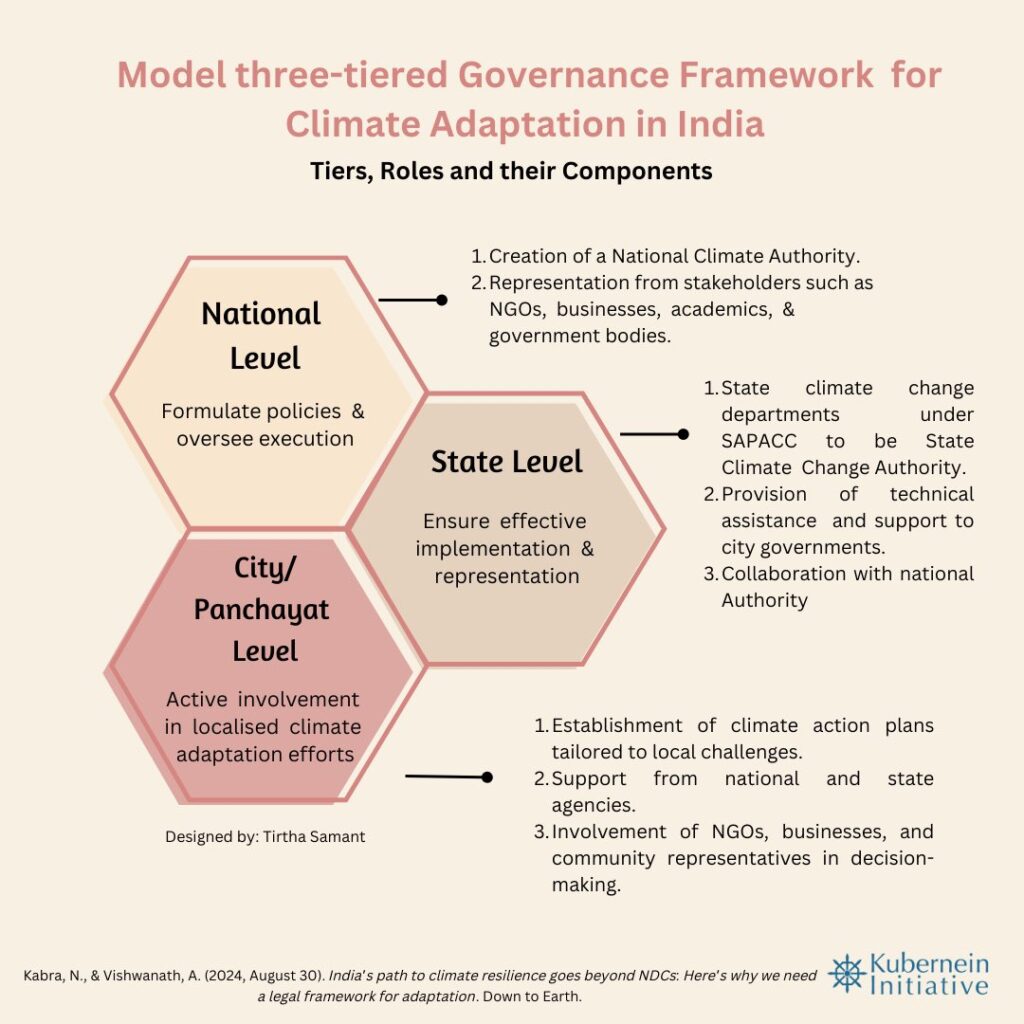

Climate actions and inactions, including policies, affect the lives and livelihoods of people on the frontlines, making it necessary to develop a participatory and decentralised approach. A three-tiered, decentralised governance framework, inspired by the 73rd and 74th Constitutional Amendments, is proposed for climate adaptation, wherein active involvement of diverse voices outside the government — including civil society organisations, the scientific community, media, think tanks, researchers and academics — is encouraged.

The legislation, akin to a climate code, needs to be a living document, with transparency, accountability and responsiveness ingrained into the system. Targets and timelines must evolve to address planning both pre- and post-recovery. The legislation can act as an enabler of climate action across different sectors, regions and communities.

In crafting a three-tiered governance institution for climate adaptation in India, drawing inspiration from Mexico’s participatory approach, a similar framework can be established to integrate bottom-up solutions, strategies and actions with top-down information sharing and financial support.

India’s distinctive quasi-federal executive system, outlined in Schedule VII of the Constitution, allocates specific functions and responsibilities to the Union and state governments for different subjects. This structure is ideal for incorporating a three-tiered governance system for climate adaptation, which could be listed under the Concurrent List, allowing both union and state governments to develop relevant policies and integrate climate adaptation across different sectors.

Climate adaptation will be a cross-cutting lens across multiple sectors and fill the critical gap in cohesive and integrated climate actions. Integrating mitigation actions, such as transitioning to decentralised energy models like rooftop solar and investing in public transport, will reduce emissions while enhancing energy security and mobility, crucial for livelihoods and economic development. Furthermore, implementing disaster risk-resilient infrastructures and climate-responsive urban planning by revising building codes to include permeable materials in infrastructure design can mitigate urban heat, water scarcity and flood risks.

The urgent need to restore and protect ecosystems, including forests and wetlands, preserve biodiversity and support community rights and livelihoods is indispensable for intersectional climate resilience. Lastly, the financial sector must support resilience through increased climate investments and insurance options to fortify communities and the economy against climate impacts. The Union Budget 2024 also highlights the need for developing a taxonomy for climate finance to enhance the availability of capital for climate action.

The urgency of legislating climate adaptation in India cannot be overstated. As climate impacts continue to intensify, a robust legislative framework will prepare us for the future. The vision for a climate-resilient India is one where proactive adaptation measures protect the most vulnerable, ensure livelihood protection and uphold the fundamental rights of all citizens in the face of an uncertain climate reality.

India’s climate adaptation law must be a dynamic and living document that evolves with changing climate scenarios. It should incorporate gender-responsive strategies, focus on safeguarding livelihoods and adopt intersectional approaches to address the multifaceted nature of climate impacts.

Additionally, it should have spillover effects on regional collaboration and manage transboundary climate risks effectively, as many of our ecosystems transcend borders. The law should outline specific detailed action plans, establish institutions for implementation, funding mechanisms and stakeholder responsibilities. Strategies for regular updates, monitoring and evaluation must also be embedded to adapt to new challenges and scientific advancements.

Views expressed are the author’s own and don’t necessarily reflect those of Down To Earth.

This was originally published on Down To Earth in August 2024.